Lolo is grandfather in Tagalog.

We were exactly fifty years and four days apart. We were both left-handed. At the dining table of my grandparents’ house, I spent my entire life sitting on his left. As a child, I would be territorial about this seat. No special guest or visiting family was allowed to sit there. I wanted to be by my Lolo.

The swiftness of a funeral is strange, only days after your loved one has passed, the family is made to do all the formal arrangements and take on the technicalities of death. The administration of it. Emotionally, we are all barreling through the first days of grief with shock, trying to measure how cavernous the feeling is.

Loving a grandparent is heartbreaking from the very start. In the last few years my grandfather was diagnosed with Parkinson’s and Dementia. His crackling wit would shine through in rare moments when his illness would subside. In the spring when my grandmother was in the hospital, I took time off to take care of Lolo, staying with him at their house. I worried about every step he took on the stairs, and I would listen for him getting out of bed. I became hyper aware of his movements around the house because I was so worried he would get hurt.

I became incensed with the bureaucracy around getting help for the elderly. How complicated it was, how they wouldn’t be able to do it themselves. Who was advocating for them? Why was it so hard? I wanted to radicalize my friends into thinking about their old age and who would take care of them. I read essays about the aging populations and the difficulties of being part of a sandwich generation (taking care of your aging parents, while also raising young children). There is a sense that no country knows what to do. I had so many questions about why our governments didn’t help more, while trying to help my family as much as I could.

Writing so soon about my Lolo feels in some ways cheap, like so soon afterwards I cannot possibly get it right. But I was asked to do a eulogy and I did not know where to begin. I wanted to write this here first and see.

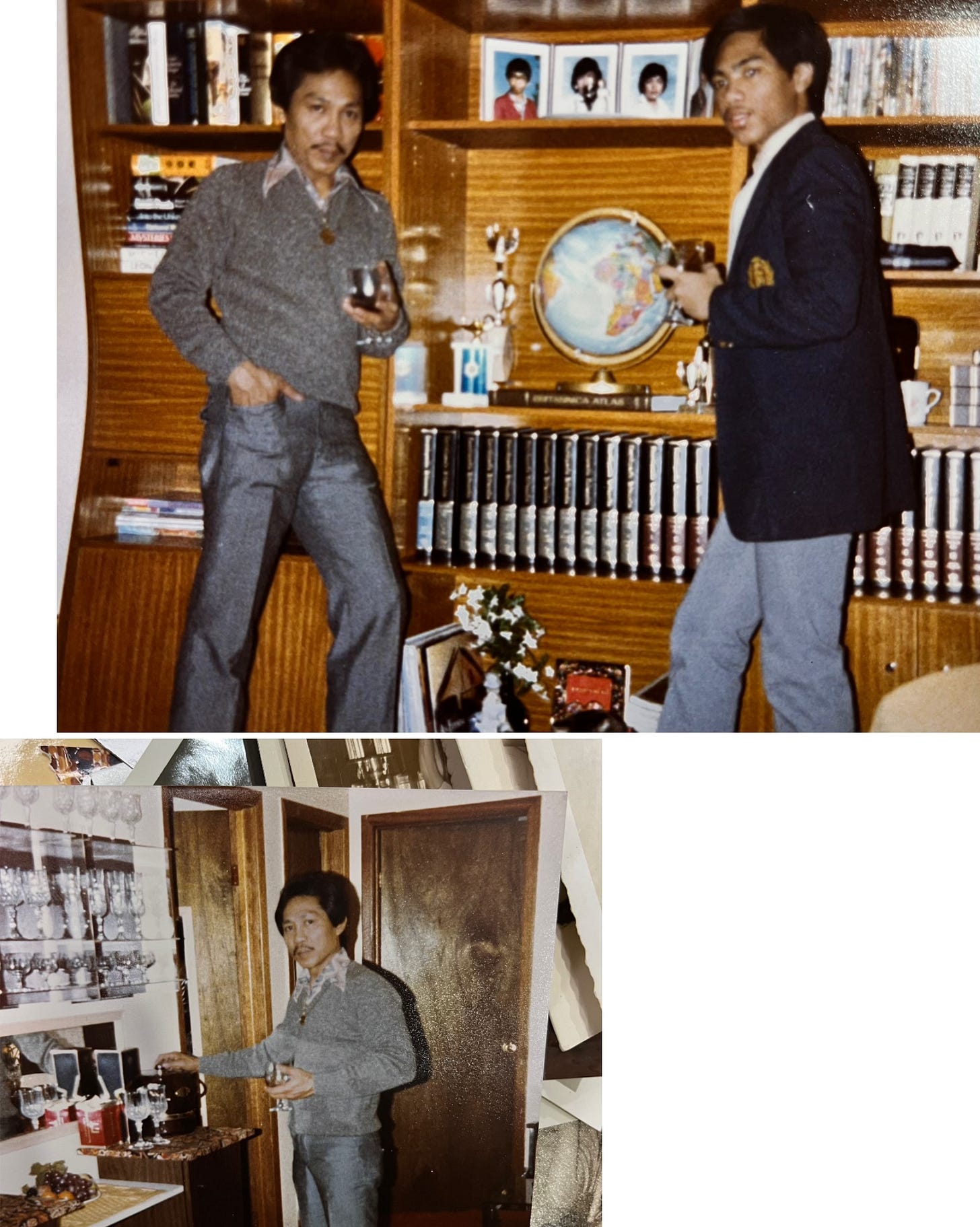

The family lore goes that my grandparents won a small sum in the lottery in the eighties, enough to put money down on a house in the suburbs and buy one luxury thing. To appease my grandmother’s hunger for a glamorous life, they bought a burgundy Cadillac. They moved their four kids from a cramped two-bedroom apartment in Toronto’s east end, to Scarborough.

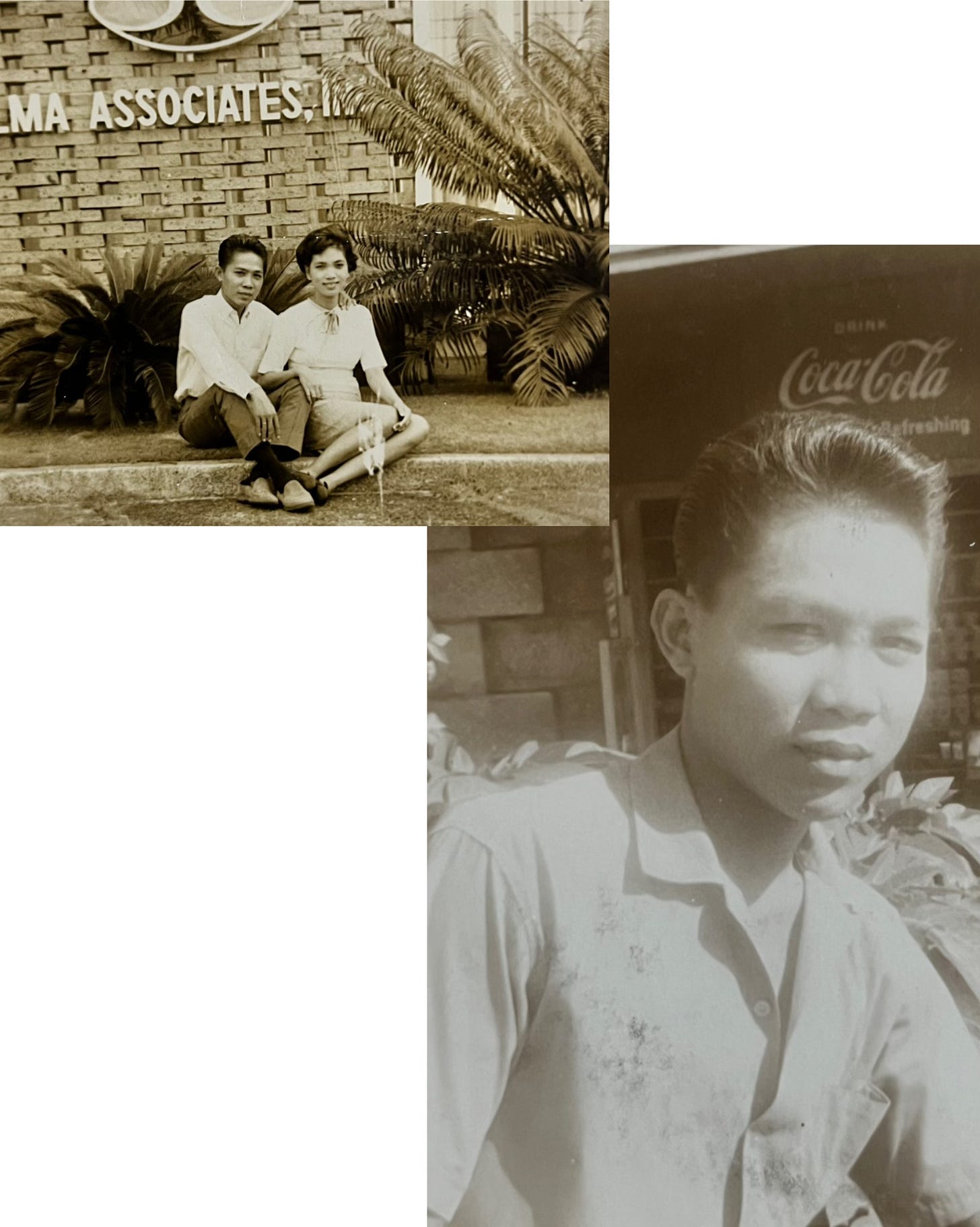

They were never even supposed to have their humble house, it took luck to get them up a rung. My grandparents moved their children to Canada in the 70s during martial law in the Philippines. There, my grandmother was an interior designer, and my grandfather made and designed furniture. After moving to Canada there were attempts to work in those same industries, but to raise their children, they would never work in their original careers again.

Lolo was my best friend. I don’t even really know how to explain it. I always felt when other kids spoke of their grandparents, it just wasn’t the same. My parents were in their early twenties when they had me and divorced soon after. When I was born, my grandparents took it upon themselves to help raise me. I was their first granddaughter. Both having November birthdays, Lola and Lolo would have a joint party each year. Once I was born, they added my name to their cake as I fit snugly between their birthdays—a household of November Scorpios. My grandfather would have turned 82 this November 13th.

He worked as a custodian at my elementary school, and we’d wake up at 6am on school days to get to his shift on time—I always made him a little late. I would sit in the custodial office flipping through newspapers and doing homework until school started. He’d go home every day to bring me lunch. I was fiercely protective of my grandfather at school, never wanting kids to make fun of him because he worked as a custodian. It hurt me thinking Lolo would ever hear.

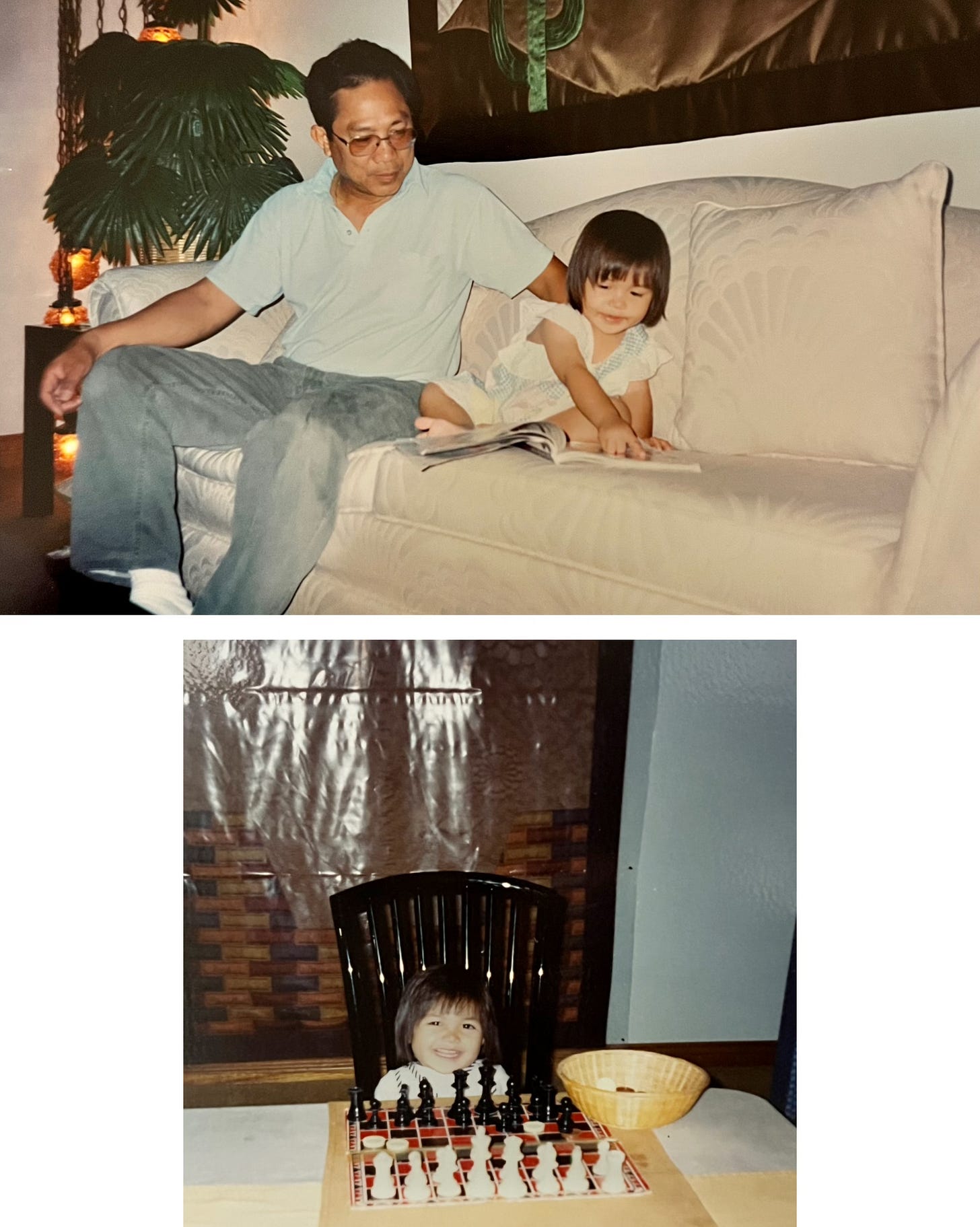

When I was little, we’d watch baseball and laugh at action films together in the dark of the kitchen. We laughed whenever there was an explosion or a fight. I can’t remember if I laughed because Lolo laughed, or he laughed because I did. He always brought me to his rank, never playing with whatever pastel toys I had lying around. He taught me blackjack, poker, checkers, and chess. I never won against him, but when I got older, I got close. I remember his exasperation at how bad I was at math. In those early mornings before school, he would write out equations for me to practice. Little did I know years later I would be doing the same thing for him—my strategy to test his cognition.

My family was filled with women who had strong personalities. My mother, my Lola, my aunt—later me and my cousins. I realized we were all this way because Lolo made room for that, he encouraged it by not pushing back. He made it safe for us to scream and shout, to be terribly difficult.

One of my favourite memories of my Lolo was when I was fourteen or fifteen. I was caught shoplifting at the mall. I remember I had just bought a vintage dress and I so wanted a thin patent leather belt for it. It had only been a few months of thievery, and my friends around me were so good at it, but I had nervous fingers. When I was caught, the store wanted to make an example. The security called the police, and a constable came in the back room to scare me with words like “Theft under $5000.” It worked. I cried and cried. The police constable told me I would need an adult to pick me up.

Lolo came to collect me from the back room. The constable had stern words for him. But Lolo said something I’ll never forget, “It was just another one of her misadventures.” Looking between me and him, the constable tried to press that this was a Serious Issue. He just nodded along, imparting that I would be dealt with accordingly. He drove me to the nearest church, and we sat in a pew, “Say a few Hail Mary’s and let’s go home.” Whenever I am in trouble, I think of his line about misadventure and can’t help but laugh.

Lolo had the best sense of humour. It was subtle and dry, with his eyes looking around for those who were smart enough to catch his joke. You’d have to be quick, and when you were you’d be rewarded with his mischievous laugh. He used this talent to diffuse oncoming tantrums from the women in his life—mostly from me and Lola.

My family talks about our foundational traits as though they were passed on hereditarily from Lola and Lolo. As though they are the source of all our personalities, much like the shape of our eyes, or the texture of our hair. From Lola I took the appetite for beauty and glamour, from Lolo I took the wit and composure. I am so thankful for that. Lolo counteracted my grandmother’s short fuse with an amused calm. When I would describe him, I always said he was cool as a cucumber. Patient, reasonable, understanding. He was the last one to raise his voice, and when he did, it would be to match the rest of us.

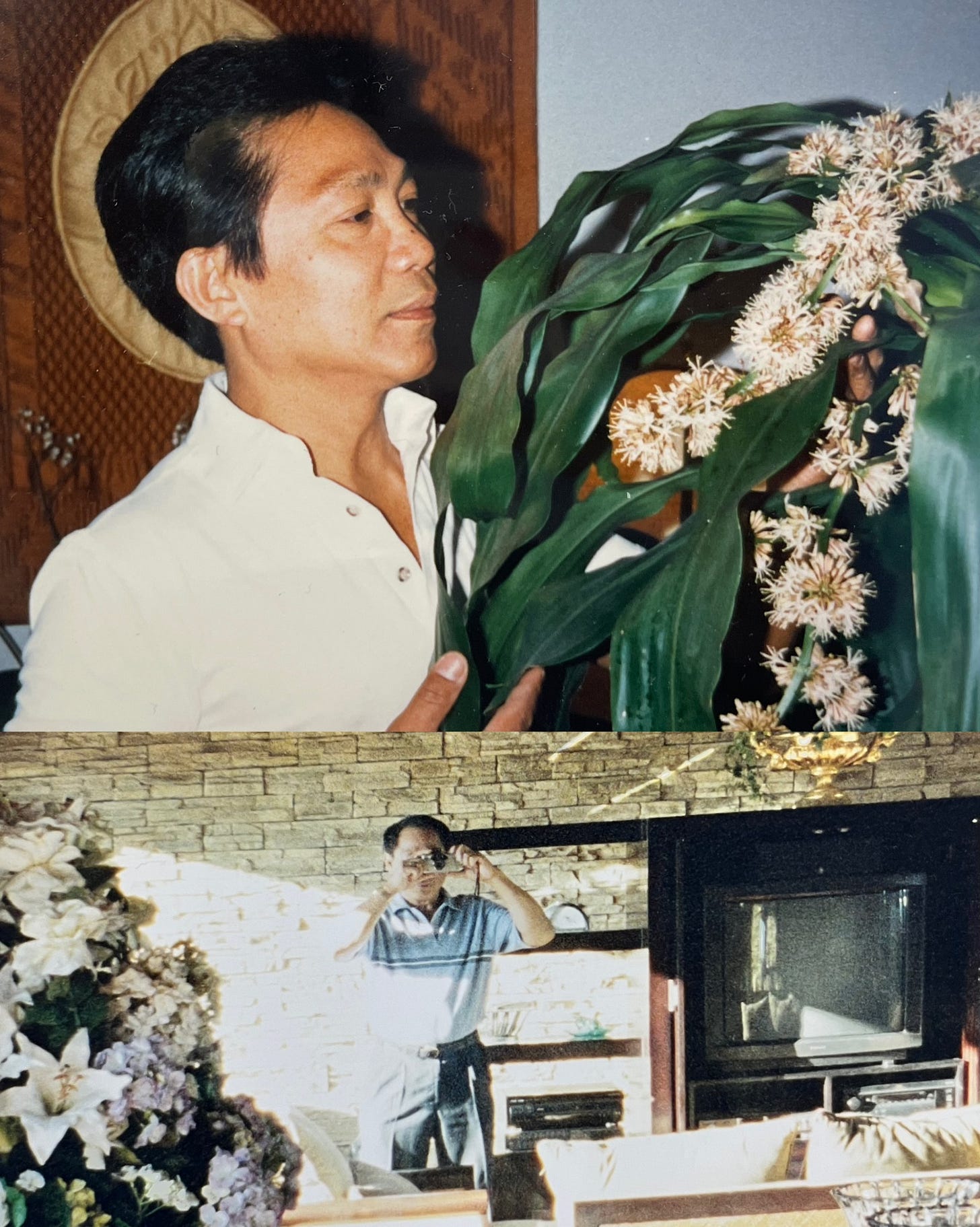

He had style, too. He had an old-world dapperness that I believed was the standard for men, only to grow up and learn I was sorely mistaken. He took it into his old age, with a cross on a long gold chain as his trademark. He always noticed what I wore and would comment to say when he found something beautiful. He’d take the textile in his hand or hold the garment up. It meant more because it came from the craftsman in him.

In some ways he was a mystery to me. There are decades of his life I know nothing about, because culturally I don’t think it was in him to discuss. He had been about getting his children, then grandchildren from one place to another. He was always answering the phone after two rings, ready to pick me up wherever, whenever. He was generous in every way.

I don’t think this is the last time I will write about him, and I will miss him forever after this.

thank you for this 🙏🏽

I appreciated reading this a lot. My grandmother died 4 years ago and it still stings--maybe because she was the only grandparent I ever got to meet. She would've been 91 also on November 13th. <3